Lights up

It’s actually hard to define consciousness. But I’d start by saying that it’s the subjective experience of the mind and the world.

David Chalmers, in Making Sense (2020)

The “easy problem”

Figuring out how the brain works in terms of its functions: How we perceive and interact with the world.

The “hard problem”

Understanding how any of the aspects related to “the easy problem” translates into conscious experiences.

Philosopher David Chalmers posits that through scientific experiments, it is relatively “easy” to explain our behavior based on stimulus-response mediated by the nervous system. For example, how the light reflected on an object in front of us is captured by our retina receptors and transmitted into our visual cortex. However, we still need to explain the fundamental mystery of why these physical processes translate into our sense of an inner universe.

What is it like to be a bat?

This is the question philosopher Thomas Nagel posed in his famous essay to present the hard problem of understanding conscious mental states from the first-person point of view of a particular organism. The paper argues that since every experience is subjective, it makes it difficult to explain consciousness objectively. Nagel argues that even if a human can imagine what it is like to be a bat, it would still be impossible “to know what it is like for a bat to be a bat.” To begin with, the way humans and bats experience the outside world is completely different.

Philosopher and cognitive scientist Daniel Dennett contends Nagel’s claim that bat’s consciousness is inaccessible. For example, we know more every day about the physical limitations of echolocation (e.g., bats can only detect objects a few meters away). Dennett argues that objective scientific observation and experimentation will eventually give us deeper clues about what it is like to be a bat. Neurophilosopher Kathleen Akins shares a similar “point of view.” In her paper “What is it like to be boring and myopic?” Akins argues that if we keep making advances in how a bat perceives the outside world, we can assume that eventually, we will know what it is like, for a bat, to be a bat.

Our self

Self-awareness is the recognition of one’s consciousness. Now, philosopher Thomas Metzinger argues that we have no self. Our ego is a mental model of our self. Metzinger describes this model as “transparent,” meaning that we are not aware of it. He posits that our model of self was shaped by millions of years of evolution, eventually leading to (exponential) cultural evolution.

The overall process was not in our interest. The self-model we have as human beings is something that brings a lot of conscious suffering into the world. It wasn’t optimized to make us happy, it was optimized to make us greedy, to have many children, to continually compete. Mother nature embedded many nasty inventions in our self-model—for instance, self-esteem, and this sense of self-worth that drives human beings forward and makes them religious and so forth. It’s important to understand the foundations of this process from two perspectives: from an internal, first-person perspective and from the third-person perspective of science. What would have been even better is if we could have a zero-person methodology, and that’s the great contribution that Asian cultures and Asian philosophy have made.

Thomas Metzinger, in Making Sense (2020)

For others, like Thomas Henry Huxley, our sense of conscious self is an epiphenomenon. Just like the smoke coming out of an old train locomotive, a by-product. Dennett goes one step beyond arguing that it’s all an illusion, that we should face it and move on.

Other’s selves

In psychology, “theory of mind” (ToM) is an assessment of our individual capabilities to understand that others also have beliefs, desires, intentions, and perspectives different from ours. In other words, empathy. Now, who are these “others” with their own personal view of the world? Are they self-aware?

Solopsychism

The view that only humans are conscious. This view usually tights consciousness and self-awareness with human language.

Panpsychism

Solopsychism is too anthropocentric. Panpsychism argues that everything has a mind. Everything is conscious at some level, from the galaxy to our cells and our atoms. We just can’t access those minds. This implies that our experience of self (our “ghost”) is a combination of all the bits of consciousness at the essential level.

Philosophical zombies

We usually associate intelligence with consciousness because we have both. However, if we were technically capable of building a robot, or a fleshy humanoid in a lab, behaving exactly like us, we would likely consider this entity as an intelligent being. Would it be conscious? Self-ware? If so, are we zombies?

Neuroscientist Anil Seth thinks that only living organisms can be self-aware. He poses that the experience of a self can only exist within the context of an organism body that needs to be actively kept alive. Hence, the brain’s main function is regulating the internal body physiology through feedback-response mechanisms, most of which we are not fully aware of. This is the reason why our fundamental experiences of self-hood, and our emotions, have a “nonobject-like character.” Seth poses that consciousness and intelligence are not part of the same package. Most of our conscious experiences relate to our physiology and emotions (e.g., fear, anger, sadness). You don’t have to be smart to feel any of these.

A sort of solo/panpsychism mixed view could argue—Chalmers says—that although some kind of consciousness is present in all basic levels, only brains have the necessary properties of unity and integration such that they are conscious and intelligent (hence self-aware?). Only brains have thoughts that can describe their minds, create a coherent narrative of the self, etc. It’s all about our ridiculous number of neural connections. We are the most conscious species on the planet because we are the most intelligent.

Snowflakes

In Stumbling on Happiness, psychologist Daniel Gilbert lays out the three main reasons each of us feels special:

(1) We might not be special, but the way we know ourselves is. We see the world from a unique viewpoint. On the other hand, we can only infer that of others.

(2) We like to think of ourselves as special. Even when forced to wear uniforms, we find ways to distinguish ourselves from the rest.

(3) We overestimate how different from others we are.

These oversights preclude us from using others as surrogates to predict our own future. By thinking of ourselves as special entities, we often miss out on years, decades, centuries of lessons learned from the experience of others.

Consciousness and human behavior

Psychologist Daniel Kahneman divides human behaviors into two groups according to the level of consciousness associated with it. System 1 activities are automatic; we are not conscious of the processes behind them. We walk by a large tree in the middle of the sunny day and expect to find a nice and cool shade behind it. A guy in a bandana speeds up his custom Harley Davidson in the street, and we expect to hear loud, repetitive explosions coming out the exhaust. In System 2, we are often conscious of what’s going on behind the doors. Someone asks us where which is our first memory. We start having an internal conversation; we look for images, sounds… sometimes consciously.

Kahneman argues that most of what we know about the world is a representation in System 1. Good. These reactive behaviors help automatize our repetitive activities. We certainly don’t want to think about each of the multiple coordinated motions necessary to park a stick car uphill in a narrow and crowded street in Barcelona. However, we must be aware that most of what we know about how things work is based on a story, told by ourselves or inherited from others (e.g., our family culture, religious preference, or lack thereof). These stories, Kahneman says, are made of complex narratives attached to strong emotions. This is why we are more likely to support one little orphan whose picture is shown to us than make the same effort to help support a fund to save thousands of children from starvation. Emotions are about stories, which are taken care of by System 1. When numbers are involved, the responsibility for action moves to System 2. However, once the emotional response is lost, the call for action also dilutes. Knowing this should help us to understand the behavior of others better and why it is so difficult to change it.

Towards the end of World War II, social psychologist Kurt Lewin differentiated two basic approaches about how to change someone’s behavior:

(1) We can apply pressure in the direction we want the other to go (threats, arguments, incentives…).

Or we can ask ourselves:

(2) Why aren’t they going there by themselves? What is preventing them from going there on their own? If we know how the world looks from someone else’s view, we might help by removing the obstacles.

Distinguishing between applying pressure, and making things easier for others, what a great idea. Suppose we can understand that we all have different scripts running in our heads. We could, perhaps, pick from someone else’s point of view.

Now, are consciousness and intelligence a matter of degree or quality? At which level self-awareness arises? Will we ever know how it is like to be a bat?

Thanks to Sam Harris for packaging fundamental contrasting ideas about consciousness in one book, it makes sense.

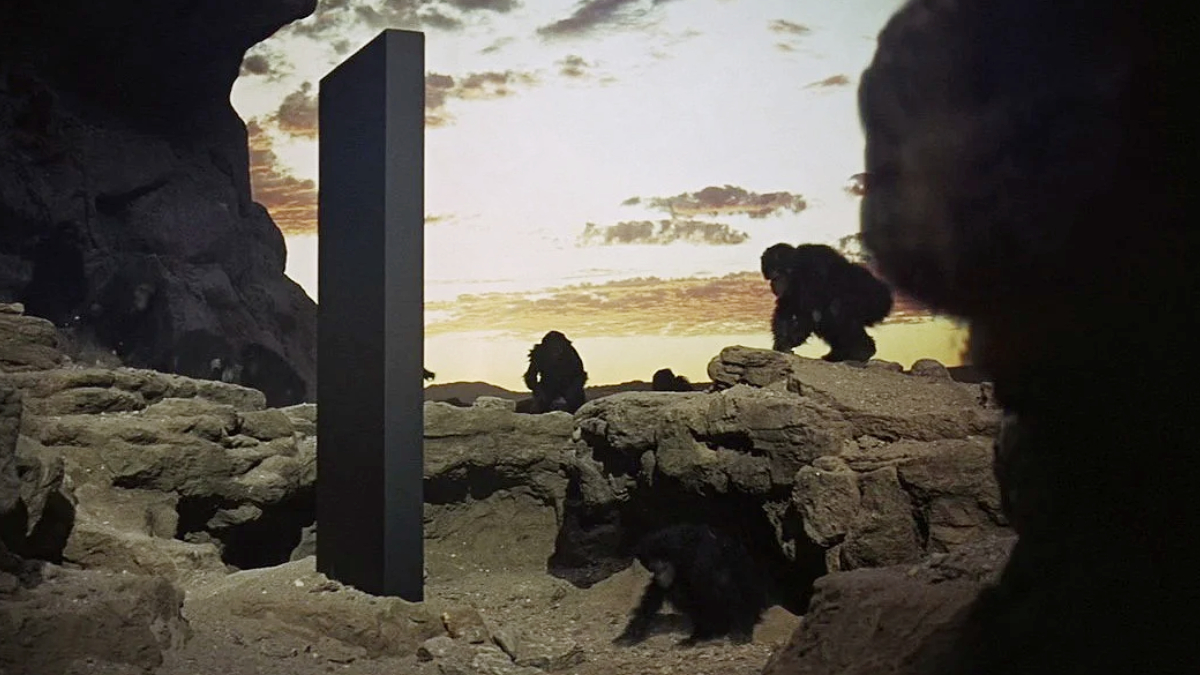

Cover image from “2001: A Space Odyssey” (credit: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer).