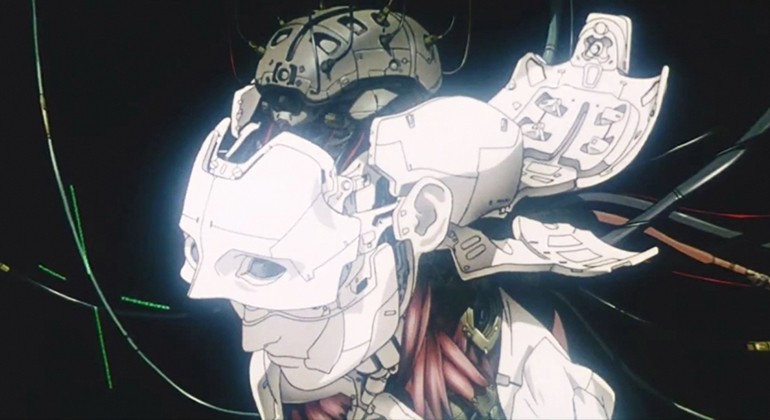

Ghost&Shell

Motoko Kusanagi is the leader of an anti-terrorist assault team working for Public Security Section 9 in Japan. The team members refer to her as “Major Kusanagi.” They follow her orders without hesitation, out of respect—even fear. They know what she is capable of. Due to a fatal accident as a child, Kusanagi depends on prosthetics to live. Still, no one would dare to consider her a handicapped person. The Major’s brain was encased in a protective interface that allows her to control an artificial body with enhanced abilities. The Major’s cyberbrain enables her to directly access any network, remotely control computers, or other bodies. Full cyborization creates existential problems to Kusanagi: Given how little blood and flesh is left in her, is the “ghost” that whispers in her head even real?

Ghost in the Shell was created by a mysterious manga artist under the pen name of Masamune Shirow. It presents a view of the complex relationships among biology, technology, philosophy, consciousness, and identity. In the end, the question asked is: What does it mean to be human? The original manga was realized in 1989 in Japan. However, the story didn’t reach international attention until the 1995 animated version was launched (by Mamoru Oshii).

Shirow’s original story (and subtitle) was inspired by Arthur Koestler’s book The Ghost in the Machine (1967). Ironically, their ideas on humankind are opposites. In Ghost in the Shell, the limits between a human being and artificial intelligence (AI) blend. In Shirow’s world, an AI can gain “human consciousness,” and a human “ghost” can live without a biological body. On the other hand, Koestler’s book was titled after the analogy coined by Oxford professor Gilbert Ryle. Ryle argued that there was no such thing as a “mind” inside a mechanical apparatus called “the body.”

The “mind-body problem” has been addressed throughout all human history by notorious names such as the Buddha (5–4th century BCE), Plato (5–4th century BCE), and Aristotle (4th century BCE). Among the “modern” philosophers, René Descartes (famously known for his “cogito ergo sum;” I think, therefore I am), defended that the mind was of a distinct nature of matter and that it could live without a body (it seems that Shirow is on the side of Descartes…). And what about the soul? The mind is commonly considered the combination of one’s thought process, reason, and consciousness. For some, the soul is synonymous with the mind. For others, the soul is the spiritual part of humankind: The mind decides what to do in order to accomplish what our soul desires.

In The Concept of Mind (1949), Ryle attached Cartesian dualism, referring to it as “the dogma of the ghost in the machine.” As a monist, Ryle believed that everything in the universe is constituted of a single unifying substance. As a linguistic philosopher, Ryle further argued that dualism was a myth derived from a semantic error, a “category mistake” in using the language. To Ryle, the workings of the mind and intelligent acts are simply the same. And to Koestler? He argued that what one senses as a “ghost,” or a mind, inhabiting the body (i.e., the experience of duality), are just signals derived from the interactions among different holons.

Koestler disguised contemporary behaviorism, which portrayed humans (and any other animal) as simple automats reacting to external stimuli in particular ways dictated by natural selection. Instead, Koestler presented a theory of “Open Hierarchy Systems” (OHS) that he called “holarchy.” Koestler argued that everything in Nature is composed of hierarchical holons, which, simultaneously, constitute a part (of a larger holon) and a whole (made of smaller holons). Each holon exhibits an integrated structure, self-regulation, and a certain degree of self-government: atoms, molecules, organelles, cells, tissues, organs, humans, societies, ecosystems,…The lower the level in the hierarchy, the more automatic the processes of its routines are (through the mechanization of habits, leading to fewer degrees of freedom).

I have tried to explain in it the general principles of a theory of Open Hierarchic Systems (O.H.S.), as an alternative to current orthodox theories. It is essential an attempt to bring together and shape into a unified framework three existing schools of thought—none of them new. They can be represented by three symbols: the tree, the candle and the helmsman. The tree symbolizes hierarchic order. The flame of a candle, which constantly exchanges its materials, and yet preserves its stable pattern, is the simplest example of an ‘open system’. The helmsman represents cybernetic control. Add to these the two faces of Janus, representing the dichotomy of partness and wholeness, and the mathematical sign of the infinite (a horizontal figure of eight), and you have a picture-strip version of O.H.S. theory.

Arthur Koestler. The Ghost in the Machine, pp. 220-221

Koestler’s theory was heavily influenced by his contemporaries Ludwig von Bertalanffy (a founder of general systems theory, GST) and Herbert Simon (a pioneer in AI research). The former considered that, biologically speaking, the notion of “individual” was a limiting one. Koestler added:

…we may regard the stepwise building up of complex hierarchies out of simpler holons as a basic manifestation of the integrative tendency of living matter.

Arthur Koestler. The Ghost in the Machine, p. 66

Koestler believed that some of the biggest challenges that humanity face (e.g., “intra-specific” conflicts such as wars) were the result of the inadequate coordination between the newly and rapidly evolved portions of the human brain and the primitive structures of the nervous system. For instance, our expanded neocortex is responsible for planning and abstract ideas (e.g., language). On the other hand, the more primitive amygdala activates the “fight or flight” responses. While the former allowed humans to develop incredible technological advances such as nuclear energy, the second made us use it against each other.

Koestler argued that machines cannot become human. However, humans can become like machines through practice and habit (think of any skilled musician playing a complex solo). Flashforward four centuries, humans are becoming more like machines, literally speaking. The production of “smart prostheses” and artificial organs benefit from new developments in AI, biomaterials, and bionics. The boundaries between humans and machines are starting to blur. In fact, actual cyberbrains are being developed now.

How far are we from the picture depicted in Ghost in the Shell? Why has this animated film reached cult status? (This anime later inspired other cult movies such as The Matrix or Avatar). The film incorporated some of the most advanced computer-generated imagery (CGI) at the time, astonishing scenography. Its soundtrack featured U2! However, tech fancies alone cannot explain the massive success of the saga. The packaging sealed the deal, but the story that Mr. Shirow created from home in Kobe revealed an itch that could be common to many humans. I know of an enthusiastic one who went as far as to study biology and the evolution of the human body for 20 years (and counting).

Are we just our biological body? Are we our brains? Our thoughts and emotions—are they merely the result of physiological reactions? Is our mind an expected neurological by-product of such reactions? Does our “ghost” exist only in the imaginary created by the latter? Or, does it shape the flame to which it whispers?

Thanks to David Alba, Marc Furió, Ashley Hammond, Santiago Catalano, Nathan Thompson, and Laia Salles Diez for reading drafts of this.

Cover image is a screenshot of the opening scene of Ghost in the Shell.