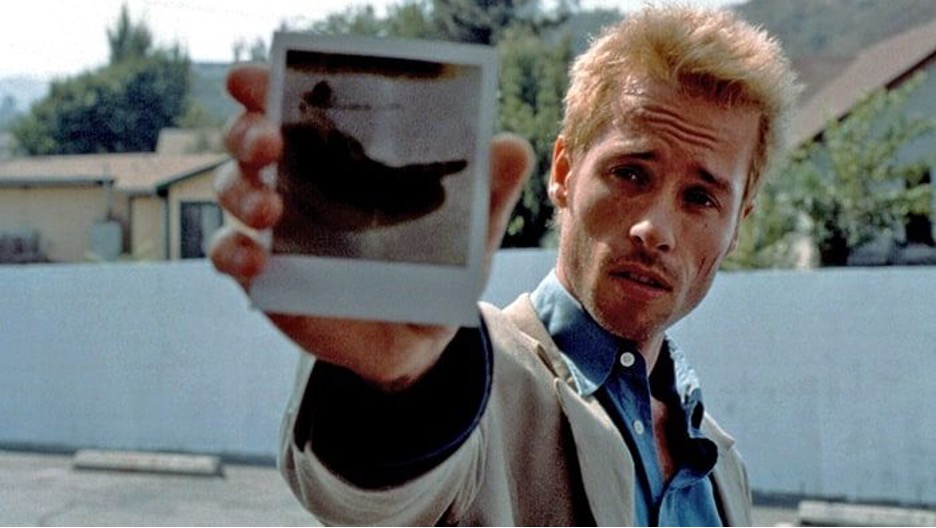

Memento

In 1904, Richard Semon coined the word “engram” to describe the neural basis of how memories are stored in our brains. Semon proposed that experiences activate a group of cells that undertake a permanent physical change—becoming an engram. After that point, every time that engram is activated, the associated memory comes alive in our minds.

Building on Semon’s theory, behaviorist, and psychologist Karl Lashley developed a series of studies to pinpoint the location of the engrams in the mammalian brain. For example, Lashley trained rats to solve the exit in complex mazes offering them rewards. Subsequently, he removed different tissue portions of the cerebral cortex in different locations and tested if the rats could find the exit of the same maze. Naturally, the rats’ memory would worsen with each procedure, but the location of the lesion in the brain did not seem to affect the memory loss. 30 years after, Lashley’s experiments did not found more clues on the matter, and the quest for the engrams was largely forgotten.

Fortunately, research on experience memory storage was not abandoned. Today, new technologies allow researchers to image and manipulate the brain at the level of individual neurons. More, the results of new studies give support to the engram as the basic unit of brain memory. But what, exactly, is an engram? In a recent review by Sheena Josselyn and Susumu Tonegawa, the authors define it as the enduring off-line representation of a past experience*. The engram is not a memory, but it provides the necessary physical environment for the memories to emerge.

Modern neuroscience indicates that there are multiple engram ensembles are distributed across the brain, as well as multiple types of memory associated with different parts of the brain (e.g., cortex, cerebellum, amygdala, hippocampus). Their specific location is likely to relate to the type of memory and its encoding. For example, the hippocampus is involved, among others, in consolidating short-term into long-term memory. Hence, damage in this brain region can impair the creation of new memories.

Enter “Memento:”

In the story, the main character Leonard and his wife are attacked at home. His wife is murdered, and Leonard suffers a brain injury in the hippocampus precluding him from creating new memories after the incident. After that point, he needs to rely on pictures, notes, and tattoos to store the key information that he needs to find his wife’s murderer. He needs to re-build his entire narrative (and life purpose) every 15 minutes.

Living screenplays

What is exactly being stored in our diffuse fleshy hard drives? Our life experiences are not like the static video clips we store on our computers and smartphones. If that were the case, our braincases would not be large enough. Worse, we would not have (or want to use) the time to recall and tell others about our experiences. Imagine having to play a two-week-long movie to explain how great our last summer trip was? In Stumbling on Happiness, psychologist Daniel Gilbert explains that we reduce full-feature experiences into simple threads such as “that place was fun,” or “food was great,” “the concert was a blast,” or just simple words “boring,” “incredible,” “short” which can be stored in our memory and more conveniently carried with us into the future.

The storyline of our past is rewritten every time we remember it. When we remember our past experiences, our brain fabricates most of the details that we experience as memories. Keywords, scenes descriptions, character names, their attitude, all that is (to a large extent) filed away.

I remember perfectly that on September 11, 2001, I was studying (rather than trying to) for my biochemistry exam the next day. I do not remember any detail of September 10. Why? Gilbert explains that rare, unusual, experiences are the most memorable. This is the reason why we tend to remember a particularly bad day, or when the line in the supermarket was ridiculously slow, but not the more frequent days in which everything went (boringly) ok. In other words, we tend to conclude that “bad” days, dates, and learning experiences are far more common than they really are. On the bright side, selecting only the best memories might be keeping our species alive. That’s why women usually remember the feelings associated with childbirth as less painful than they actually were, Gilbert poses.

Our brains use facts and theories to make guesses about past events, and so too do they use facts and theories to make guesses about past feelings. Because feelings and theories do not leave behind the same kinds of facts that presidential elections and ancient civilizations do, our brains must rely even more heavily on theories to construct memories of how we once felt. When those theories are wrong, we end up misremembering our own emotions.

Daniel Gilbert, Stumbling on Happiness (2006)

Memories it’s all we’ve got

We are at the movie theatre, the plot is tight, the tension high, the s/hero is about to complete the journey’s circle, and the moron in front of us takes a call on his cellphone. Years later, what precisely are we going to remember about the two-hour-long event?

Psychologist Daniel Kahneman also remarks that memories and experiences are not the same. We all want to be satisfied with our life. Therefore, since our full-feature experiences are remembered only as re-re-re-constructed plots based on selected keywords, we go around not trying life good experiences, but trying to keep anticipated good memories. Because our brains store memories in such a particular way, there are some aspects of human behavior that are here to stay.

Our memories are a misrepresentation of our past, based on a few remarkable events. The narratives of our present situation are after the fact constructions connecting the dots that we get to keep. Given all of this, can we possibly predict our own future? Well, if we actively decide what’s worth remembering, can’t we decide the direction of the story?

*Engram definitions, based on Box 1 from Josselyn and Tonegawa 2020:

Engram

Enduring offline physical and/or chemical changes evoked by learning and underlie the newly formed memory associations.

Engram cells

Populations of cells constituting the critical cellular components of a given engram. These cells can also be key components of engrams supporting other memories. Engram cells are (1) activated by a learning experience, (2) physically or chemically modified by the learning experience, and (3) reactivated by stimuli present at the learning experience, resulting in memory retrieval.

Engram cell ensemble

Collection of engram cells localized within a brain region. Engram cell ensembles in each brain region are connected, forming an “engram complex,” which is the entire brain-wide engram supporting a memory that is stored in sets of engram cell ensembles in different brain regions connected via an engram cell pathway.

Thanks to Jonathan and Christopher Nolan for writing “Memento” (see still of Leonard in the cover image above), and for throwing me into this rabbit hole. As Christopher Nolan says, this story only exaggerates a behavior common to all of us.